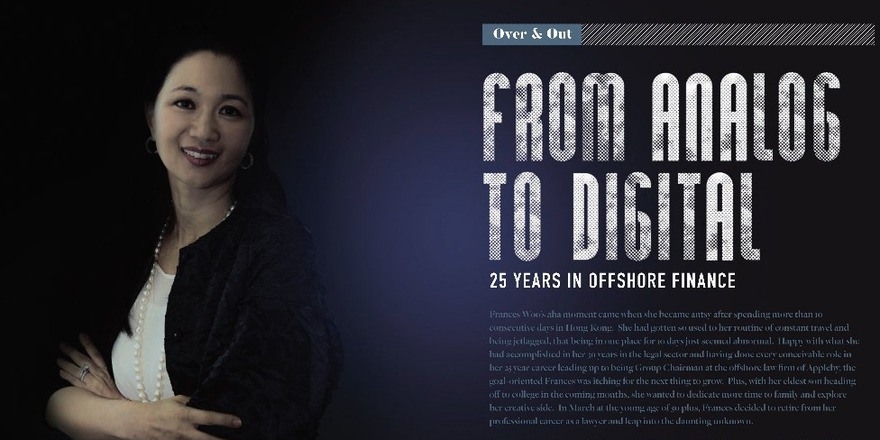

Frances Woo’s aha moment came when she became antsy after spending more than 10 consecutive days in Hong Kong. She had gotten so used to her routine of constant travel and being jetlagged, that being in one place for 10 days just seemed abnormal. Happy with what she had accomplished in her 30 years in the legal sector and having done every conceivable role in her 25 year career leading up to being Group Chairman at the offshore law firm of Appleby, the goal-oriented Frances was itching for the next thing to grow. Plus, with her eldest son heading off to college in the coming months, she wanted to dedicate more time to family and explore her creative side. In March at the young age of 50 plus, Frances decided to retire from her professional career as a lawyer and leap into the daunting unknown.

Recently she sat down with Director of BVI House Asia Elise Donovan and gave her insights from 25 years in the offshore financial services industry.

Elise Donovan:

I was really inspired when you gave your farewell presentation at the reception, and appreciate your taking the time to talk to us today. Can you give us some background on how you started in the industry?

Frances Woo:

Thank you very much for having me here, Elise, and allowing me to share that with you. It has been very gratifying and rewarding to be part of the offshore financial industry.

When I first started on this journey, even as early as an undergraduate at university, I never thought I would go into law. I did my undergraduate in toxicology and pharmacology. Most of my family had a background in the medical sciences. My father was a surgeon and many of my role models tended to be in the sciences. There were not too many people in political science or in law or the humanities and so that wasn’t something I thought I would get into.

It really all happened when I was in university and I got my first job at a law firm as a receptionist over the summer. From that time I gained a lot of insight into law, and one of the partners there took me under his wings and then suggested that I apply to law school, which I did. I recall that when I was admitted to law school in Canada, which, like the US, is a graduate degree program, my father said to me, “Lawyers are a dime a dozen.” He wasn’t very happy. He considered it a second rate profession.

But I persevered, and being from a science background, I really thought I would go into environmental law or maybe intellectual property or patent. As it turned out, there was a recession in Canada, and after I did my articling, the positions that were available were in corporate law and finance, and so that’s where I went.

How I got into the financial industry, and offshore, a lot of it was serendipity. None of it was planned. Very much is made of the saying, “If you’re given lemons, make lemonade.” It really was that, going with the flow, and adapt and change. I practiced a number of years in Canada, on Bay Street in a very large national firm. But then I felt I wanted to get more international exposure. I wanted to spend a year or two abroad before I got too old, and a number of my law school classmates said, okay, let’s write the Qualified Lawyers Transfer Test to qualify for England and Wales. At that time I had a choice whether to sit the exam in London, New York, Toronto or Hong Kong. I said, let’s go to Hong Kong and make a trip out of it. That’s what we did, and so I came here and sat the QLTT, having no intention to search for a job outside Toronto.

Then I went back to Toronto, and at that time Appleby was looking to recruit. I was thinking, unbeknownst to them, that perhaps I would follow the job to Hong Kong and then see what else was available. I did not want to practice Hong Kong law prior to the handover because I did not know what would happen, and I did not want to practice English law because I didn’t have ties to the UK, either. So I thought the best thing for me was to practice something a little more international.

ED:

So, you moved from Toronto to Hong Kong with Appleby. What was the environment at that time?

FW:

The environment was extremely narrow. Very, very small. I would say that, when I first arrived, there were only two offshore firms, Appleby and Conyers, and even so, Conyers had two or three lawyers and Appleby had one or two lawyers. From the onshore legal industry, practicing offshore was not at all well respected. It was almost as if you couldn’t cut it in mainstream law, therefore you went into offshore. Everybody was very perplexed, and puzzled, why you would choose that route. It seemed to be more of a dead end. It wouldn’t get you anywhere. The feeling was, once you went offshore, you could never get back onshore.

So it was very, very different from what it is now. People felt it wasn’t really a specialist area in and of itself. Also when I arrived in Hong Kong, in the early 90s, Hong Kong itself was very colonial, British companies and institutions dominated. Equally, it was a time when a lot of the international companies were rotating a lot of their executives on secondment every two years, every three years. It was also a time when a lot of the Hong Kong practitioners, the Hong Kong financial industry was still developing. Most of the business in the early Nineties was conducted in English – British English. There was a smattering of American English and North American English. Towards 1996 everyone was preparing for the handover and a lot of the meetings began to change, from focusing on English to focusing on Cantonese, because at that point a lot of the local Cantonese who had been working at British law firms and British institutions, as well as international companies, were becoming more senior and they began conducting meetings in Cantonese.

ED:

So the handover from British to Chinese rule in Hong Kong in 1997, would you say, was a major impetus for change in the industry? For example, you said there was a stigma attached to working in offshore law, and it’s not there now. Did the change happen organically with the handover?

FW:

Yes, it was partly with the handover, because the handover was the impetus for a lot of the development. But in Hong Kong the financial services industry was growing more rapidly, becoming more sophisticated, more complex. It was also at the time of the opening up of China, and Hong Kong acting as China’s window to the world.

So as China business became more complex, so too were the types of offshore structures that were required. For instance, starting from the mid 1980s you started seeing many of the offshore companies being utilized for listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Then the BVI worked for a lot of the intermediary companies, for a lot of the holding companies. And then you were seeing offshore used in the bond market and in structured finance deals. And as financial services became more sophisticated, offshore had a greater role to play as an intermediary facilitating a lot of these transactions, to translate what was being done in China through to Hong Kong, and from Hong Kong out into the international markets, whether they be in New York or in London.

It was also at this time, through the 1980s and 1990s, that London started the rapid growth of its role on the international scene. As you look at the 1970s, the 1980s and the early 1990s, New York also grew in terms of its internationalism. So with all of these factors happening in tandem, I think that very much assisted the offshore industry globally, but certainly in Asia, in coming out from being stigmatized to a greater appreciation and understanding of its role.

ED:

Could you talk about how different things were in the beginning for you, working with a typewriter, for example.

FW:

It was very challenging when I first arrived in Hong Kong, because it was before the internet age and before email. I am of that generation where I straddled both the analog and the digital. But having to be the interface with offshore, many of which were, like BVI, Cayman and Bermuda, based in the Caribbean time zone, and dealing with clients in Asia, with demands and urgency and getting things done like yesterday, and dealing with the lack of technology, was very challenging. When we had to send reams and reams of documents for filing or registration, we would have to stay there feeding pages into the fax machine into the wee hours of the morning, sometimes finding out that at page 383 the fax had stopped transmitting. Then you’d have to make a long distance call to find out how many pages had been received or not received, and if they hadn’t been received, you’d have to start all over again at page one, feeding in one page at a time. It was also very time sensitive. In terms of communication, sending things by post might take two or three weeks before you got word back. You were really a satellite, and nobody really thought of you and what your challenges were here in Hong Kong.

So there were a lot of things you had to do independently, and you had to improvise, innovate and shoot from the hip a lot.

ED:

With all of those challenges at the time, why did people want to do business offshore?

FW:

It was challenging, but the challenges people faced were not the same challenges that people faced in mainstream law with the financial institutions, because most of them had a lot larger presence here that they could draw upon, and they were very focused on Asia, so they didn’t have to do deal with an interface. But people wanted to work with offshore because there were a lot of advantages. So places like the BVI had right of appeal to the Privy Council, dealing with the law of England and Wales, with a lot of statutory interpretation on top of that. There was a lot of political stability. And there was a lot of familiarity, because BVI law was similar to Hong Kong law, pre-handover and post-handover, as a matter of fact.

BVI law was also very streamlined, and administratively not unwieldy, versus Hong Kong law, which was very unwieldy. If Hong Kong wanted to make any quick changes, to adapt to any trends or developments in international business, they couldn’t do it, because they weren’t as flexible or as nimble as the BVI with any of the developments that international business required.

Also, offshore learned very early that they needed to reach out and understand what the trends and the needs were. Therefore, they had their tentacles on the ground in Asia, versus international business, which said I’m a temple, come worship where I am. So the fiduciary providers were on the ground very early to facilitate that.

ED:

What have been some of the highlights in your 25-year career?

FW:

There have been many. Just coming to Hong Kong was an amazing experience, and seeing the growth in the financial industry and changes in language use was also a real highlight. Certainly, the handover and the Asian financial crisis were big deals.

Prior to the handover there was a lot of nervousness, a lot of concern, but equally a lot of anticipation of what the handover would be like, what changes it would entail for Hong Kong and how the international community would view Hong Kong after the handover. But it was almost anticlimactic because once the handover had occurred in July, then very soon after that there was a market crash. For Hong Kong, it was the first crash they had experienced in a very, very long time. For a lot of the Hong Kong elite and business executives, many of whom were taking over from international businesses and especially British businesses moving back to the UK, it was quite a shock, and people had to scramble in terms of how they coped with it, deploying a lot of the structures and action plans that they had developed. That was quite memorable.

Also memorable was becoming a partner at Appleby in 1997 and then a managing partner in 2000. Even prior to that, I think the highlight was being able to practice the laws of various offshore jurisdictions. Because that meant having a broader understanding and a broader appreciation of how the offshore industry fit together, rather than from a narrow lens. I think that brought a lot to bear on each of the offshore jurisdictions that we worked with, because then we could say, look, we’ve seen this in other offshore jurisdictions. And slowly, beyond the offshore jurisdictions that Appleby covers, we were equally able to see what was happening in places like Lichtenstein or Singapore or other offshore places that would bring intelligence and information to other jurisdictions that we represented.

And then of course the different roles I played in management and ultimately becoming Global Chair of Appleby in 2014. That was very much a heavy and demanding global role that I played, but it was very fulfilling in terms of being able to interact with clients and with the industry in all of the places where we had clients.

ED:

It sounds like things happened for you naturally, or in some cases, as you said, it was serendipity. But at what point in time did you set your sights on the pinnacle?

FW:

At no point did I set my sights on the pinnacle! For me, the ethos, which came from my father, was 90 percent hard work and 10 percent talent. Do things with a lot of integrity and to the best of your ability and really, give your best and full heart and attention to it. I think over a period of time I recognized that I had a lot of institutional knowledge, and there’s a legacy to that.

Once you’re involved in how the industry or how your firm develops over time, then that in itself is also very helpful. If you have an interest and a passion and enthusiasm in what you do, and you’re vocal about it and you want to participate in various projects, then people tend to want to find workhorses to do those things, and over time you generate respect. It’s not something that happens overnight. It’s not something that I ever thought when I first arrived in Hong Kong that ultimately I would want to be global chair of this international law firm. Even in 2012 and 2013 I really didn’t think I wanted it, but it was my fellow partners who were encouraging me to play that role. I guess maybe they saw I was doing those things already.

I think that at every point of what I wanted to do I had mini goals and a mini action plan, and things that I wanted to see and improve. I was always interested in law, not just from a narrow lens, but what law did and how it integrated and how it was implemented and assisted in getting the results the business community wanted.

ED:

You’re one of the few women I know who became global chair of an international law firm in the financial services industry. What advice do you have for women?

FW:

Just empower yourself, be confident, be passionate, and do not be afraid of going for whatever it is that your goal is, because you will find a way to make it work. I think a lot of the concern, particularly for women, and even for some men, so I don’t want to generalize in that way, but they’re always very worried that they can’t meet expectations or exceed them. Have the confidence to do that and embrace your ambition, and then find a way to make it happen, as opposed to self-doubt and worry that you won’t meet expectations. There are all different types of role models out there, and there’s no one size that fits all. Make it your own, as opposed to, I need to fill the shoes of someone who did it this way. That’s why if you take up that role it’s going to be unique, and it’s really because you bring in your own characteristics and your own stamp to it. That’s what people are looking for, and that’s what international business needs: disruptors, innovators, people who are looking at it from a different perspective. If they’re looking for the same old same old, then they can grab the same old same old, and nothing is going to change. That’s my take on it, not that I knew that as a young person. Don’t stop trying, keep pushing the boundaries.

ED:

What was your inner motivation? Did you have a mantra you kept telling yourself? What drove you? We all have challenges and self-doubts, but what made you overcome those obstacles?

FW:

From a very young age I’ve had a lot of training in developing resilience. If you had the father I had, you would be very resilient. I played a lot of competitive tennis as a young person. Then I played varsity tennis for my university. I think sport probably helps you with a lot of that, developing the mental toughness that you need. So part of the motivation is always seek to do your best and try to push that envelope. Another motivator is pride in your work, and also fear. Fear is a motivator, not necessarily the most positive motivator, but it’s there in the background and you need to recognize that. Other positive motivators wouldn’t be accolades or recognition but the feeling of a job well done. The ability to collaborate with others, to see the final goal and bring others along with you, is what I enjoyed.

ED:

How do you build diverse teams effectively?

FW:

Through a real interest in understanding people’s backgrounds and what motivates them, and a love of different cultures, and loving to collaborate. I’ve always felt that to be an excellent leader you can’t dictate. Yes, the stick is there, but to get a team that is really going to perform optimally, it really needs to come from their heart. So I spent a lot of time on buy-in, on discussion and collaboration. And when you’re devising your projects on collaboration and how to measure them, those have to be properly aligned. A lot of time is spent on listening and allowing others to talk. It helped me that I came from a Western upbringing but also had, three or four generations back, immigrants, and was a visible minority. But, truth be told, when I first landed in Hong Kong I hadn’t had a lot of exposure to the UK and European cultures, so I spent a lot of time trying to understand them, and it turned out that at Appleby a large proportion of our fellow partners are from the UK or European. I tried to understand their backgrounds, their sense of humor, the various classes in the UK, all of that, coming from Canada was not natural, so I needed to understand the sensitivities around that as well. In the offshore jurisdictions sensitivities to race and gender and language.

ED:

And the Asian culture.

FW:

Yes. Understanding that and a lot of the nuances attached to that. For somebody that is new to Asia they would think there is just one culture. And it is not. It is a very complex cornucopia of cultures. Even within Southeast Asia it’s all very different. Even for Chinese speakers it’s very different. For someone from Hong Kong who is a Cantonese speaker it’s different than for someone from the Mainland, who is then very different from someone who can speak the language but who might have been raised in England, or in the US or from Taiwan. I love those differences – they’re absolutely fascinating.

ED:

Do you think you were able to bridge them because you come from both worlds?

FW:

Yes, I definitely felt that. The other day my youngest son was saying that sometimes as a third culture kid he doesn’t fit in. I said, you know what, at no point have I felt I ever fit in 100 percent anywhere. But I think that’s a strength. It means that wherever you are, you turn on the facet that allows you to fit in the most. And that allows you to go somewhere else and turn on a different facet that allows you to fit in. I think that’s okay because at the end of the day we are all unique. The fact that you’re not going to be comfortable 100 percent of the time I think is good, because that means you continue to try to comprehend, and learn and understand. So my acting as a bridge was definitely one of the features that helped.

ED:

What advice would you give to young people, seeing what you’ve seen over the last 25 years?

FW:

I fully acknowledge for young people today it’s very challenging because innovation is happening at such a pace that we never experienced. But I guess if you go back 100 years, 100 and 50 years, our previous generations had a tough time too. At each moment in time they will encounter their unique set of challenging environments or opportunities. So I would say, for a young person wanting to go into the financial services industry, identify what area you’re passionate about or that you’re interested in. Don’t just look at it as a means to an end. And then when you identify that area, think all you can about that area and show your enthusiasm, that passion, whether you’re going to university or you’re finding your first job. Because wherever you go, people are seeking those kinds of people who they see can bring the organization to the next level. It’s not just about talk (I’m going to do this) but you’re already doing it and the organization can see that you’re doing it,so they will naturally give it to you. They can see you are already in the saddle and participating. If it’s something that’s yet to be done, then volunteer your time. Also be interested in how things fit together, rather than looking at things through a narrow lens. Offshore is by itself already very niche, so you need to find a way how offshore can help or fits in, or how it will sell to international business. That means you really need to be quite current on developments or even ahead of the curve on developments. You need to read and talk to people.

ED:

What do you see as the disruptors in the industry?

FW:

Definitely technology. Artificial intelligence is happening at a fantastic pace. The digitalization of everything, even when you are talking about law or the financial industry, the pace at which they can use artificial intelligence to consume information, to analyze it, and also to learn how to make decisions, is happening. Humans or mankind will need to find a way to make a difference from an emotional aspect rather than purely an analytical aspect. I can see that as being very much a disruptor. What that means is that a lot of the labor intensive technical review of documentation or a technical review of the latest fund, those are going to be replaced. Never mind manual labor. So in the next 10, 15, 20 years it’s going to be very difficult to predict what the next big professional career is going to be. That means that it’s all the more important to stay ahead of the curve. Governments need to be that much more nimble in predicting.

ED:

What else besides technology is driving the offshore financial services industry in the Asian market?

FW:

Going back three or four years Asia benefitted from being a little bit insulated from the developments that were happening in the UK and in the US by way of FATCA, CRS and other developments. Certainly in the past two to three years, as Asia has become more and more integrated, they are less insulated. That and the fact that China is going outbound, it’s more difficult for them to be insulated. On the political side, all these developments that you are seeing – the US pulling out of the Paris accord, and the US pulling away from the TPP, it means that Asia is more and more on the rise, particularly China, in terms of its role and reputation on the world stage. So that means it’s difficult for Asia to be insulated from international regulations and demands. There’s been a lot of pressure on the offshore industry in terms of OECD, FATCA and CRS, but in a way it just means that offshore will be narrowed, there will be less competition and there will be an elite stable of offshore jurisdictions that will be well recognized and blue chip. Equally, there will be more of a hybrid that’s developing in offshore between the onshore / offshore space. That means some of the onshores will be taking on some of the offshore characteristics and offshore taking on more of the onshore hybrid characteristics in order to comply in the race to become blue chip jurisdictions.

ED:

How do you see the BVI performing?

FW:

The BVI is in a very strong position in Asia, and has had that position of ubiquity and volume during the past five to seven years of increasing sophistication in the use of the BVI. Having said that, I think the BVI is at a crossroads now in terms of where it wants to take the next phase because it is very, very clear to me at least that it cannot rest on its laurels. So it needs to innovate and disrupt quickly. In a way it’s in a strong position because Asia is still growing and developing and China is very dominant in terms of its position on the world stage both economically and politically as well. So how does the BVI align itself in assisting China and Asia and achieving Asia’s own growth plans, in a strong and reputable manner. That will probably entail continued investment and staying power by the BVI. But it also means that because of limited resources it’s very difficult to put too many eggs in all the baskets. You need to have the conviction to stick with the plan, whatever it is, and enhance dialogue on that stage. There’s a lot to play for, just look at China’s Belt and Road Initiative. That’s huge in terms of the infrastructure and investment that’s running west all the way through Asia to Europe. There’s a lot the BVI can do to assist and aid and participate. That’s part of the BVI bank trying to assist in getting over that hurdle. It’s also engaging with tax practitioners to educate them, and also speaking with private banks and getting them to understand. It’s good to band together with the offshore community, it’s only in that way that you can have a stronger and louder voice, particularly when you are combatting onshore and governments’ inclination to increase tax revenues.

ED:

So what does the next chapter look like for you?

FW:

I think right now I’m just focused on taking a bit of a breather. I have a number of priorities that I have long neglected, including family and parents and a bit of travel. After that it’s a really open world for me. I’m trying to discover it and embrace it.